How Many Cryptic Crossword Grids Are There?

Counting the number of valid American-style crossword grids is more or less a solved problem. For example, see this FiveThirtyEight Riddler and Michael Kleber’s answer in a Twitter thread.

However, the same doesn’t seem to be true for British-style cryptic crosswords. Hence this blog post!

Now, counting the number of valid grids is a different task from enumerating them, and it’s a bad idea to do the former by doing the latter, because the sheer number of grids can be prohibitively expensive to compute. However, I’m mostly interested in grids smaller than 11×11, and I actually wanted to see all possible grids, so I went ahead and did the inadvisable.

So let’s jump right in! If you’re just interested in the numbers and a list of all valid grids, feel free to scroll to the very end.

What Makes A Valid Cryptic Grid?

- The grid must be rotationally symmetric.

- The grid length (i.e. the length of one side of the grid) must be an odd number.

- All white squares must be connected: that is, there can be only one contiguous island of white squares.

- All words must have half their letters checked.

- For words of odd length, there’s some ambiguity: depending on who you talk to, either “half rounded up” or “half rounded up or down” must be checked.

- For the purposes of this blog post, I required “half rounded up”.

- There cannot be more than two consecutive unchecked squares.

- Two consecutive unchecked squares cannot occur at the start or end of a

word.

- I haven’t found much explicit mention of this rule other than this blog post saying that it’s a “house rule” at The Times of London, but all cryptics I’ve seen have hewed to this requirement, so I enforced it.

It’s also worth noting that different constructors and publications have different “house rules”. For example:

- Some publications have upper and/or lower limits on the number of clues. For example, the Financial Times seems to always have exactly 32 clues.

- Some constructors also restrict the size of black islands: for example, there cannot be a contiguous black island of more than five squares.

I didn’t enforce these rules, more out of laziness and lack of time than technical infeasibility.

Generating Cryptic Grids

Akshay Ravikumar has an excellent blog post explaining how he generated American crosswords, and if you’re interested in diving deeper I highly recommend reading his exposition: my algorithm is more or less directly lifted from his work, just adapted to cryptic crosswords.

Here’s the final algorithm that I used:

- Precompute all

valid_rowsandsymmetric_rows: for a cryptic, these are rows that don’t have words below the minimum word length. - Using

valid_rowsandsymmetric_rows, find all sets of valid middle three rows — for example, for an 11×11 grid, find all possible fifth, sixth and seventh rows.- Note that the middle row must be symmetric, and the two adjacent rows must be mirror images of each other.

- From the middle rows outward, build up a grid in a depth-first search.

- Before adding a new row, make sure that it satisfies the checking requirement: that it has the correct number of unchecked squares and has at most two consecutive unchecked squares not at the start or end of words.

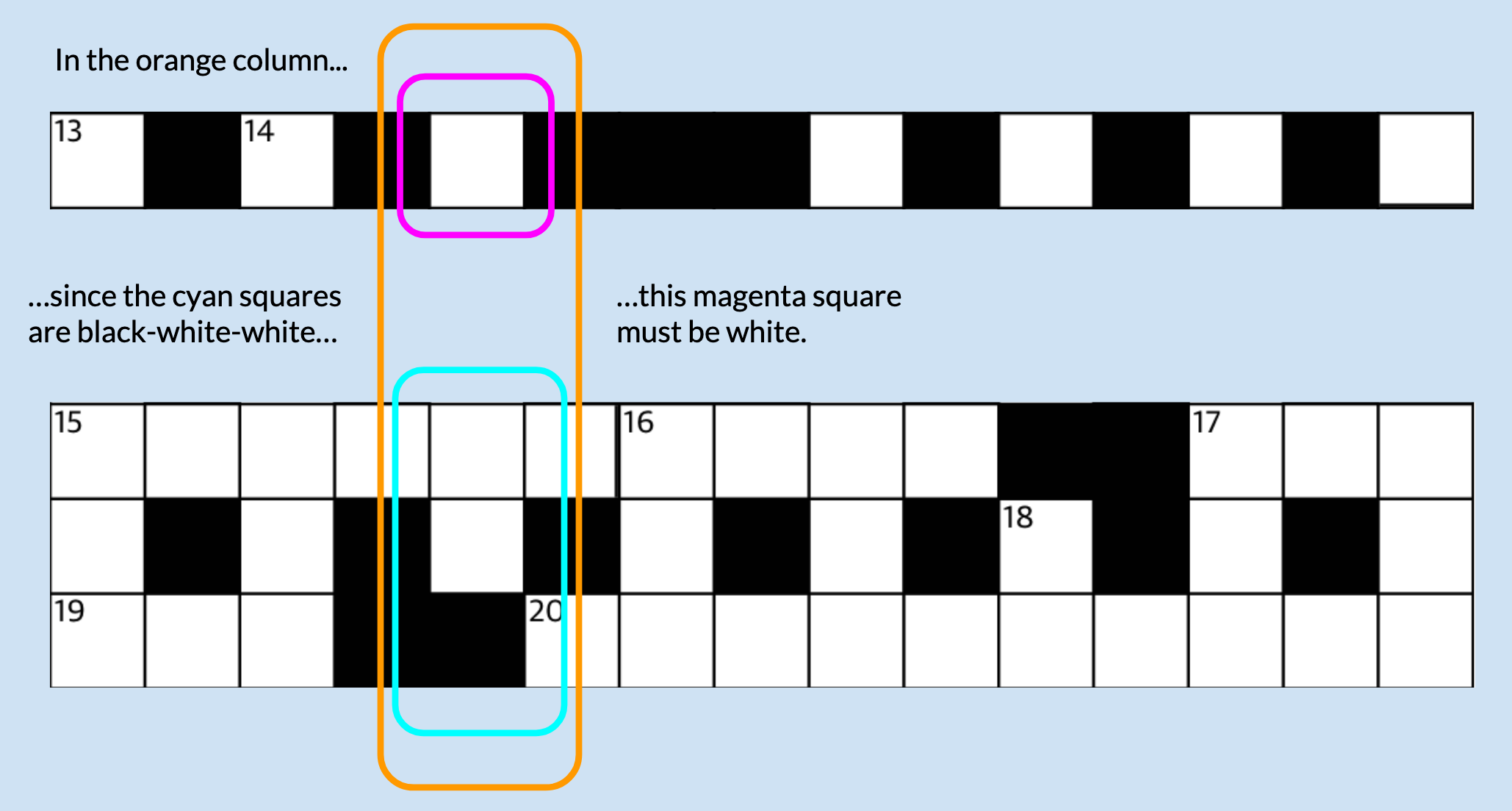

- There is also a trick we can use to limit the search space: if the previous three rows have a column that is black-white-white, then in the same column, the next row must be white.

- This is best explained pictorially:

- Check that the columns are valid. Specifically:

- Check that the columns are

valid_rows(this ensures that there are no words below the minimum word length). - And also check that the columns don’t have two consecutive unchecked squares at the start or end of the word.

- Note that all other requirements (e.g. the number of checked squares) are already taken care up while building up the grid.

- Check that the columns are

- Check connectedness of the grid using a depth-first search.

This algorithm works well and runs reasonably quickly (i.e. in less than a minute) for 5×5 and 7×7 grids, but at 9×9 the search time becomes significant (around half an hour on a MacBook Pro). Additionally, some valid grids aren’t very interesting as “real” crosswords, such as the one below.

⬛⬛⬛⬛⬜⬜⬜

⬛⬛⬛⬛⬜⬛⬜

⬛⬛⬛⬛⬜⬛⬜

⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜

⬜⬛⬜⬛⬛⬛⬛

⬜⬛⬜⬛⬛⬛⬛

⬜⬜⬜⬛⬛⬛⬛

It’s not very interesting because of the sheer number of black squares (and

correspondingly low number of clues). So to winnow down the grids more, I

filtered valid_rows before I start: valid_rows must have a minimum number

of white squares: 2 squares for 5×5 and 3 squares for 7×7 through 13×13.

Anecdotally, this reduces the computation time by a factor of three or four. I

call the grids produced in this reduced search “interesting grids”, as

opposed to “valid grids”.

I should note that there are definitely more ways to speed up the search: I could’ve parallelize the search (i.e. assign each worker a subset of the valid middle rows), I could’ve written the program in a language faster than Python (like Julia), and further algorithmic speedups are possible (e.g. checking columns after adding each row would prune more grids earlier, instead of deferring the column checks to after the grid is constructed).

At any rate, I just ran the program on my laptop, and stopped at 9×9 grids. Results below!

Results

If you’ve just scrolled down here, the only thing you need to note is that an “interesting grid” is one in which every row has at least a certain number of white squares: 2 for 5×5 grids and 3 for 7×7 grids onwards.

For comparison, I’ve added the number of valid American grids, taken from Michael Kleber’s corrected Tweet.

| Grid Size | Valid Grids | Interesting Grids | American Grids |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5×5 | 17 | 9 | 12 |

| 7×7 | 346 | 43 | 312 |

| 9×9 | 9,381 | 334 | 31,187 |

| 11×11 | N/A | N/A | 17,438,702 |

| 13×13 | N/A | N/A | 40,575,832,476 |

| 15×15 | N/A | N/A | 404,139,015,237,875 |

There are 346 valid 7×7 cryptics — interestingly, slightly more than the pleasing 6 × 52 = 312 valid American-style crosswords which inspired Malaika Handa’s 7xwords; disappointingly, factorizing into a not-at-all-auspicious 2 × 173.

For larger grid lengths, there appear to be far fewer valid cryptic grids than American grids, probably owing to the more stringent conditions for cryptics.

It was infeasible for me to run my program for 11×11 grids onwards — either I need to put a lot more effort in optimizing my program, or (more likely) it’s simply computationally intractable to enumerate all possible grids, and we can only count them. If I’m inspired to pick up this line of work again, I’ll be sure to post a part two!

And finally, the code: